Sri Pada: A Religious Site of Contestation and Co-existence

Excerpts of Sir Ponnambalm Ramanathan Memorial Lecture delivered by Premakumara de Silva, Ph.D Professor, Sociology and Anthropology Department of Sociology University of Colombo, on 12th January 2017, at the University of Jaffna.

|

|

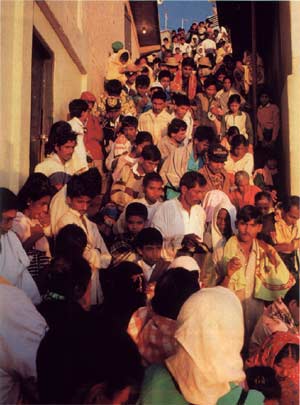

On a poya (full moon) day in the pilgrimage season, the crowds on the steps to the peak can be so great that pilgrims may stand in a stationary queue for hours.

|

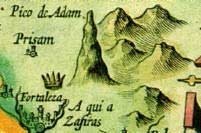

Now, let me briefly talk about my work on Sri Pada (Sri Pada) which is a major pilgrimage site in the country that is also known to the English-speaking world by its Anglicized name "Adam’s Peak". This tropical forest mountain territory (samanalaadaviya) is said to be protected by the god Saman, considered the guardian of Sri Pada. Historically speaking, Sri Pada is a remarkable place of worship for people belonging to all four major religions in Sri Lanka where they share one particular object of worship, the sacred footprint, but with specific interpretations from their own religious traditions.

In my view, such difference traditions were evidently tolerated at the pre-colonial Sri Pada, which had been continuously patronized by the pre-colonial states. Though Buddhist monks had controlled the Sri Pada temple and Buddhist kings lavishly patronised it, alternative religious belief and practices were never excluded from pre-colonial Sri Pada. Instead, they were accommodated and recognized.

Like other major pilgrimage sites in Sri Lanka thousands of pilgrims annually make the journey to Sri Pada to worship the sacred footprint. In the past, many people climbed there with the intention of acquiring religious merit and indeed today they visit for many reasons. The main pilgrimage normally takes place during the months of December to May, however the busiest part of the year extends from February to April, with the peak of the pilgrimage season during the festival of Mädin full moon day in March.

|

|

The historical development of the site showed how different Sri Pada Temples have constructed, reconstructed or ordered, and reordered under different powers at different historical moments in temple history. It is also evident that Sri Pada has been historically viewed as a multi-ethnic and multi-religious site and how that multiple discursive and non-discursive practices have been contested and marginalized with the insurgence of the Sinhala Buddhist Nationalism, particularly in postcolonial Sri Lanka. Though all sorts of ‘bitter’ disputes, contestations, antagonism and exclusion have been transpired in the ‘official’ domains at Sri Pada Temple, the continued attraction of the large number of ‘pilgrims’ mainly from ‘peasant and working class backgrounds’ of all nominal religious affiliations is remarkably impressive. Obviously, the majority crowd is represented by the Sinhala Buddhists, the largest religious group in the island.

Unlike other Buddhist pilgrimage sites on the island such as Kandy, Anuradhapura, Muneswaram, and Kataragama, Sri Pada pilgrimage has never been abandoned despite the political difficulties that have arisen since it was firstly institutionalised as a popular pilgrimage site during the kingship of Vijayabahu I in early 12th century. The factors that have affected the attendance numbers, and led to occasional breaks in Sri Pada’s popularity, have been insurgencies, outbreak of epidemics and unexpected weather conditions. Pilgrimage to Sri Pada has otherwise remained a popular attraction to many people in Sri Lanka regardless of their religious faiths. The impact of such afore-mentioned factors on the popularity of other pilgrimage sites is no way comparable with that of Sri Pada pilgrimage.

The Sri Pada that was created in the decades after Independence does not represent a return to any original condition that it inherits. Rather, it was a new creation – a predominantly Buddhist space – a very concrete manifestation of current ideas of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism. Like Kataragama, the strong Buddhist element at today’s Sri Pada continues to grow. The smaller number of pilgrims who are representing non-Buddhist religious communities are still present at the Sri Pada temple as subordinate groups to Buddhism.

The paradox of politics and nationalism in modern Buddhist polities is particularly acute in Sri Lanka, a historically multicultural and multi-faith island where four great world religions – Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Christianity, a range of indigenous spirit beliefs, and astrology, have coexisted for centuries. Though the island’s Sinhalese majority, who are mostly Buddhist, have been in a bipolar ethno-linguistic conflict with the Tamils who are mainly Hindu in the post-colonial period (1983-2009), most Buddhists pay homage to Hindu deities and Buddhist temples have Hindu shrines. Indeed, religious co-existence and hybridity among Sinhala Buddhists and Tamil Hindus in everyday religious practice, has been as much a unifying and bridging factor between these communities, as a dividing one since the rise of post-colonial Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism. Though the post-colonial conflict on the island is primarily ethno-linguistic, public religion or Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism has been used by a range of political actors to marginalise religious minorities. I have explained this point through the case of Sri Pada temple particularly how Sri Pada lost it historical base of plural worship at the advent of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism in (post) colonial Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka’s cultural diversity and complex mix of identities is not unique. Most South Asian nations are plural, diverse and complex. However, in the post/colonial period diversity has been perceived as a threat rather than a gift. The result has been marginalization and discrimination against smaller and less powerful groups for linguistic, ethnic, religious, caste and/or class basis, giving rise to various forms of violent political conflicts. Since independence, however, there has been a failure to define and realize an inclusive national vision from the perspective of this distinctive heritage. Instead, competitive ethnic and religious politics became institutionalized.

In this paper I have described Sri Lanka’s multi-religious nature through its major religious sites, but made a case for the idea that some religions in the country have had, or currently have, an eminent position in respect to the other religions as they have enjoyed at different times a favoured relation with political power. This favoured relation has not always been a strict correspondence between state and religion, for as I showed during the pre-colonial even colonial periods with the Sri Pada example, the state was quite receptive to the existing social and religious diversity of the country but that receptiveness began to be challenged when national culture was increasingly dominated by a highly politicised and organised Sinhala-Buddhist polity.

That receptivity was, however first challenged by the Portuguese Catholics who transformed this situation by destroying temples and eventually evicting the Muslims from law country regions. But then they gave way to the Protestant Dutch, who themselves gave way to the increasingly secular bureaucratic British who created a colonial state, and a native bourgeoisie that inherited power and a plantation economy as well as a religiously revitalised diverse society that has increasingly demanded that the majority religion be granted the foremost place. This has not been achieved easily or without bloodshed, because the foremost place for Buddhism in Sri Lanka entails the territorial capture of both space (and time-sound) within which the minority religions can exist and co-exist as long as they acknowledge and subordinate themselves to Buddhism. My speech also explains that many of the major religious sites have been shared among Sri Lanka’s diverse religious communities as often as they have been contested. If these sites and the divinities associated with them are permanently Buddhicised, they will cease to be viable sources of divine justice for all groups concerned just as much as the state is no longer viewed as a neutral agency serving everyone on the basis of common citizenship, equal human rights and human dignity.

With this conclusion I would like to thank you again for this opportunity to address you, and to do so when celebrating the life and work of Sir Ponnambalm Ramanathan, whom I regard as one of the National Heroes who admired multi-culturalism, religious tolerance and co-existence. Of course on top all that he was a visionary thinker and a great human being whom we can proudly say ‘a true Sri Lankan’.

Courtesy: The Island of January 27, 2017