|

|

Saman Deviyo as depicted at Kelaniya Vihara

|

|

|

Offering brought to Saman Devale, Ratnapura

|

|

|

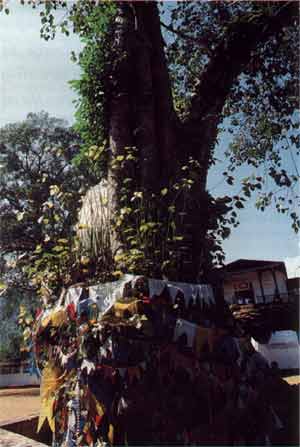

Offerings left at the Bo tree at Maha Saman Devale, Ratnapura

|

|

|

Saman Deviyo statue being brought in procession from Maha Saman Devale to Sri Pada at the beginning of the pilgrimage season

|

|

|

Building that houses the holy footprint at the summit of Sri Pada

|

|

|

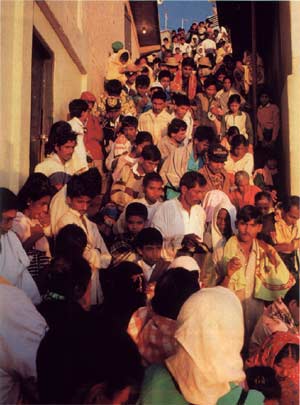

On a poya (full moon) day in the pilgrimage season, the crowds on the steps to the peak can be so great that pilgrims may stand in a stationary queue for hours.

|

|

|

Next to the holy footprint hangs a bell that each pilgrim is

entitled to ring as many times as he has climbed the sacred mountain.

|

Visiting a God

The god Saman sometimes teaches life lessons by playing on pilgrims' expectations as they climb to his abode atop Adam's Peak

At the 2,243-metre-high pinnacle of Adam's Peak, there is a "holy footprint", for which the mountain receives its Sinhala name, Sri Pada. But whose footprint is it? Buddhists believe it is Lord Buddha's. Hindus say it is Shiva's; Muslims, Adam's; Christians, Saint Thomas'. With Hindus worshipping Buddha as an incarnation of Vishnu, and both Christians and Muslims revering Adam, it is not always clear exactly who the protagonist is in the many legends that swirl around this holy peak.

Perhaps it doesn't matter. Whoever stepped down from Heaven to leave this footprint in stone, as many as 250,000 pilgrims per month leave their own, more transitory, footprints on the Earthly approaches to the Buddhist monastery atop Samanalakande — to use yet another name for the peak, the one that reminds us that it is the abode of the god Saman. But who is this god Saman? The answers that scholars offer are bewildering in their variety, which I find appropriate following my visit to this mischievous but good-humoured god.

Sri Pada is part of the main watershed of Sri Lanka, from which her four largest rivers spring. South and east of the peak are found the rubies, sapphires and emeralds that earned Sri Lanka the ancient name of Ratnadvipa, or Island of Gems, which has been identified as Sindbad the Sailor's Valley of Gems.

The peak is a perfect pyramid and a remarkable sight, visible from far out in the Indian Ocean. Though Sri Pada was described by travellers early in history, the first to report the existence of the footprint was the Arab Soleiman in 851. The first European to describe the peak first hand was Daniel Pathey, a German serving in 1648 as a soldier in the Dutch East India Company.

The pilgrim has the choice of starting from the village of Maskeliya, on the eastern slopes above Hatton, or from Ratnapura, southwest of the peak. I chose the latter because, though longer and steeper, it is the classical route.

Arriving in the gem city of Ratnapura, I checked in at the Kalawathie Hotel, which has a wonderful botanical garden and facilities for Ayurvedic treatment, herbal bath and massage before and after the climb. These are important because otherwise the effort can leave your muscles aching for at least three days.

Then I paid a visit to Maha Saman Devale, the largest temple devoted to Saman, to prepare for my pilgrimage. In the outer wall of the compound is the famous stone showing a Portuguese soldier killing a Sri Lankan nobleman, perhaps the king of Jaffna. The historic but fading frescoes inside the temple show Saman with various accessories—sometimes a lotus, sometimes a bow and arrow—but always with his "vehicle", the elephant.

In the main hall hang veils brought by devotees in gratitude for a cure or other wish fulfilled. The afternoon I visited the temple was an auspicious one, and several young couples had brought their newborn babies to be blessed for the first rime by the devale priests. These priests, called kapuralas, are neither the Hindu Brahmins they resemble nor Buddhist monks, their origin predating the arrival of either religion. Even today, this priestly post is passed from father to son.

Walking around the temple, I saw a gorgeous view of Samanalakande that made the mountain seem fairly close. That was the first time God Saman deluded me.

I didn't want to walk the entire 27 kilometres—with its altitude gain of more than 2,000 metres—so at 9pm I started driving from Ratnapura toward Carney Estate, from where it is a seven-kilometre climb. I missed a turn in the darkness and perceived my error only when the narrow road went from bad to worse. Already Saman had fooled me twice. I turned the car and sped back down the hill. Soon I saw a line of lights wending their way up the hill. This was the day after Unduvap Poya Day, and a nearly full moon still bathed the tea estates and distant mountain ranges in a soft silver light.

I had chosen that day because on full moon days the path to the peak becomes so crowded that one sometimes has to stand in a stationary queue for hours before moving slowly on. In the event, I found myself to be the only pilgrim in sight. I was a little shocked. It was 10.30pm by then, and the loneliness, together with the wildness of the landscape, scared me.

Friendly employees from the Wildlife Department allowed me to park my car in their fenced courtyard and promised to watch it through the night. As I walked through the lanes of the sleeping village, I saw only one shopkeeper, and even he was asleep on his counter—possibly to ensure that his goods would still be there the following day, or perhaps because he had no other place to sleep.

The village was brightly lit, but there were fewer lights as I came to the paddy fields at its edge. I had a wondrous view over the low-lying fields and the tea estates perched further up the slopes in the bewitching softness of the moonlight. The path grew steep as it led into the darkness of the jungle, most of the light bulbs having been burst by heavy rain. The stone steps were sometimes half a metre high, and small brooks cutting across the path made it slippery. I chose my steps carefully. I had to pause often, and once I sat — or rather lay—on a bent tree. Such was the silence that, when I looked up to see what was causing the only sound I could hear, I realized that I was listening to the gentle gliding of a leaf upon the air.

Later, in a place of absolute darkness, a loud noise exploded close by. Fed by stories of wild animals on these slopes, my imagination ran riot. I saw myself trampled by an elephant, torn to pieces by a bear or devoured by a leopard springing from his lair. It took me several minutes to calm my nerves—even though my rational mind knew that almost all of the wild beasts had long since been driven from here.

As I climbed and grew increasingly tired, Saman continued his tricks. Three or four times I thought I was nearing the top, only to emerge disappointed on a dark plateau, the god mocking me from his abode high above. Clouds swirled round the peak, reflecting the bright lights there.

When it started to rain, I reached my deepest low. I sat down on a stone and pondered. I calculated that I had covered only about half of the distance, with the worst to come, but already my strength was gone. What was I doing here on this mountain in the middle of the night, when anyone with a modicum of common sense would be in bed?

Most Westerners reach this point of despair when climbing Sri Pada. Some turn tail. Others make it to the top out of shame, surrounded as they are by 70-year-old pilgrims calling "karunawai, karunawai("compassion") or " Saman Devindu, api enava" ("God Saman, we are coming"). But I enjoyed no such encouragement. To be joined by a few pilgrims would have been enough, but for hours I had not met a single human being. I fell into a deep hole of despondency and indecision. On the one hand, I feared mockery if I returned to the hotel in the morning. On the other, I normally wouldn't give a farthing for the good opinion of others.

Then I remembered for whom I was doing this: for myself and none other. If I could make it, I would. If not, let it be. I had been so attracted to this mountain, and to the stories I had heard about Saman, that I would now accept whatever happened. I arose with renewed strength and slowly continued on my way. Out of the blue came the certainty that I would reach the peak, no matter how long it took.

I'm convinced this new energy was connected with Saman. I later spoke with the chief lay custodian of the Ratnapura temple, a man named Tennekoon, who told me that Saman granted pilgrims what they had in mind. Sometimes he fooled them, as when his gifts became unexpected burdens, but he never did any harm. I had gone to meet the god curious and a little sceptical of all the powers he was accorded in the stories told by village folk. But Saman taught me a life lesson.

I don't really know what my expectations were, but my long attraction to Saman and my years of anticipating my pilgrimage up Sri Pada had surely left me ripe for an extraordinary experience. This is what happened. Still exhausted, walking slowly alone in the silence and peace of the night, breathing deeply and concentrating on my footing, I fell into a state of awareness like that of meditation, in which I noted the coming and going of ideas without judging them. Images and thoughts formed, then vanished, and in this way the story of my life flickered before my inner eye like a movie. Chapters that had lasted years in reality passed in a moment, and shorter episodes lingered in my mind. It was a thrilling stroll down the lanes of my memory—not all of them pleasant—from childhood to adolescence, adulthood and retirement. It seemed that someone was hauling up to my consciousness people and events I had forgotten for 20 or 30 years or longer.

Sri Pada, which I knew I would climb only once in my life—if at all—became my final goal. This revealed to me hidden connections between events in my life, the "why" and "how" of my arrival on this mountain, as though my life had followed a secret plan. When I resisted it, fate dealt me a blow; when I surrendered, everything flowed as easily as water downhill. The details of this inestimable experience are too intimate to relate here—and anyway would be of interest only to me.

I reached the peak at 8 am. There the Buddhist monastery clings to the rocks like an eagle's eyrie, the holy footprint (larger than that of a man) in a small building at the highest point. Next to it hangs a bell that each pilgrim is entitled to ring as many times as he has climbed the sacred mountain (one man tolled the bell nearly 50 times that day). There are rooms in which pilgrims can rest, protected from the chilly wind, if they have climbed in the night to see the sunrise.

The peak's outline emerges in the soft light of dawn and, as the sun climbs in the sky, Sri Pada's triangular shadow sharpens, then shrinks slowly toward the base of the mountain. (As I arrived too late for the sunrise, I saw this only in photographs.) The breathtaking 360-degree view reaches from the Indian Ocean to the hill country around Kandy and Nuwara Eliya. Far below, the town of Hatton emerges like a cluster of doll houses amid reservoirs and wewas (tanks). From time to time, the interplay of rain, clouds and sunshine creates multiple rainbows. The peak does indeed feel like the abode of a god, high above the petty problems of the mundane world.

I paid my respects to the loku hamduruwo (chief incumbent) and started back down the mountain. Along the way, I overtook an impressive Hindu wearing a sarong, his hair wound up in the classical conde, a fashion that is dying out. He carried a beautiful baby in his arms and had just cleared an extremely steep passage where one hardly dares to peep into the abyss. He asked me where I had come from and where I was going. "I am glad that you made this pilgrimage," he said. "It is good for people of all races, religions and ages to come here. I just introduced my four-month-old daughter to God Saman, asking him to protect her all her life." Then he silently and gracefully continued along his difficult way.

A little later a group of four pilgrims came up. Two men were helping and sometimes carrying their mother, a woman in her 70s. A third son followed carrying devotional gifts for the god: flowers, fruit and coconut oil. They told me that this was the old woman's 15th pilgrimage to Sri Pada and that she intended to continue visiting Saman every year until her death.

Hard as the way up had been, the walk down was even harder, because the leg muscles are better suited to climbing than descending. Soon my knees began to shake and my thighs became hard as stone. I had to sit and rest more and more often. Once an old man, who was plainly quite poor, saw me sitting on a rock and noticed I had no food. He interrupted his climb and offered me one of the five biscuits he had bought in the village far below. I thanked him but could not accept his offer. Instead we shared my last cigarette. Then two men came along, each climbing with a large sheet of corrugated steel on his head, and this made me wonder how long it would take to build even a small house this close to Heaven.

I reached my car in broad daylight, hardly able to move, but happy. I had not slept for more than 24 hours, and on the road back to Ratnapura, I dozed off behind the wheel—twice. The first time I nearly rammed an oncoming car; the second time I almost went flying off the road at a sharp curve. Was this Saman telling me not to forget him?

By Goetz Nitzshe

From Serendib magazine Vol. 16 No. 3 May-June 1997